On the day of the festival, I arrive with the children – a busload of exuberance and anticipation. The bus climbs slowly up a rocky dirt road. I can see the years, generations, and centuries of work in the shape of the mountain itself- carefully terraced with stones, stacked with care to hold up ancient and prolific olive and fig trees, surrounded by herbs used to make the local blend of Za’atar Dukka.

I am in the West Bank of Palestine, invited by Fidaa Ataya, to take part in the Festival of Forbidden Life, created by the Jabal Al Risan art collective in an effort to preserve culture, gather the community, and lay claim to the land. I have never traveled to the region before, and the one thing I know for sure is that I don’t know what I am getting into. Should I book a hotel? “No,” Fidaa told me, “You will stay with my family. Take the bus through the checkpoint to the very last stop and then take a taxi. Tell the driver the name of my family – there are no street addresses.” I take notes and keep them close, but hidden, in case my bags are inspected. “Don’t lie about where you are going,” her friend advises, “but don’t tell them you are coming to the West Bank.”

Last year, Fidaa and her collaborators founded the heart of Al Risan Art Museum (h.A.R.A.M.) or “haram,” meaning in Arabic “forbidden.” Al Risan is a mountain in Area C, across the valley from 3 villages in Area B, where Fidaa and her family have lived for generations (What are Areas A, B, C?). On this mountain, the h.A.R.A.M. museum is a space, without a brick-and-mortar structure, where artists come together to restore hope, create culture, share stories, and foster community- not only for themselves but for their families and friends, neighbors, and colleagues. They note that the primary artist in their collective is the Jabal Al Risan mountain herself. The art works are in the open air- some tangible (a set of scarecrows reported to come alive at night), some not (“1948”). Those meant to be lasting often become unintentionally ephemeral, transformed by violence (a beautifully carved cornerstone smashed to bits) or displaced, like their makers.

It is increasingly difficult to get up the mountain. There are huge holes in the one dirt road that accesses the land, apparently dug by hand and capable of ruining a vehicle, if you don’t know to avoid them. I can only imagine how long it must have taken to dig that hole now that I feel for myself the hardness of the rocky soil. Fidaa tells me the Settlers do this little by little, and that last week they beat up a mother and child who had come to pick olives on the mountain. Many local families have stopped going to their land for fear of being attacked. In many areas of Palestine’s West Bank, Settlers have been destroying the olive trees, and with them the harvest, the economy, and an entire way of life (See also The Ecologist). We carefully avoid the potholes and arrive at the festival, spilling out into the sunshine.

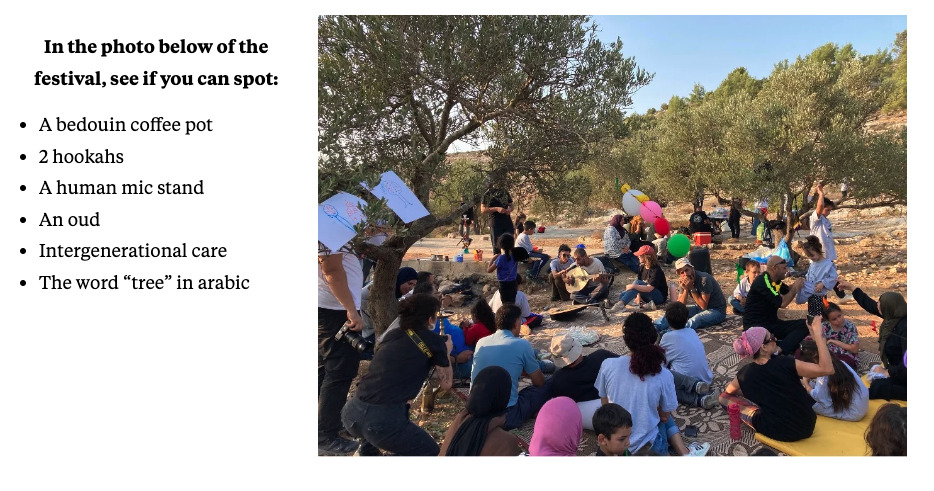

The festival strategically applies strength in numbers, responding to fear with art. Here on this beautiful clear day, art is in its happy place- creating joy, peace, unity, and hope for the future. The performances bring people together, share the values and way of life of a people through culture, and bolster their resilience with joy. Farmers, villagers, and their children come together and sit once again under their beloved olive trees. A farmer teaches us how to plant trees in the dry, rocky soil- using pickaxes and watering them in. We bring water from the well, an essential resource. Today, there are restrictions on building cisterns and many existing ones have been destroyed by the Israeli military. We used the water for the donkeys, for watering the trees, for cooking, and for washing. The planting of trees is central to the festival- a commitment to life on the land and to caring for it, even as they are barred access and piled with restrictions- no structures, no buildings, no freedom.

Palestine Journal (Emma Jaster, 2022)

Artists and guests from all over Palestine and the world participate and perform. Although many who plan to come are barred access through checkpoints, those who do make it give their all to the festivities. Osama Diab leads us in traditional and popular songs on the oud, Kavalia leads yoga. We all enjoy a Dabke dance, and a fire dance by Nar Omar, from Jerusalem. Shorooq and Nhaia produce delicious meals for the masses, cooking on rocks and over tiny open fires. We share maqluba, shakshuka, flat breads with za’tar and coffee made in the bedouin style. There is a craft activity for the children- making pictures out of pieces of nature- twigs, olive leaves, and dried flowers and a traditional embroidery workshop from the local women’s collective. The children star in a donkey fashion parade and an open-mic. They pose and sing songs, clambering enthusiastically for the mic, for the opportunity to be heard, to express themselves, to sing their culture and their heritage, to exist freely as themselves.

Festival of Forbidden Life (Emma Jaster, 2022)

Just up the hill, I can see the rooftops of settlers’ houses. Three households who seem to have the military on speed dial. While the settlers’ actions appear on the surface as petty and puny- stealing rocks from a mountain made of stone, digging holes in a dirt road, pulling up saplings- their actions are all backed by the U.S.-funded and armed Israeli military.

The military interrupts the Festival 3 times in person, once by helicopter, and more or less constantly by phone and text to the organizers who had secured permission for the event in advance. I ask about our safety as the helicopter buzzes low and slow- could it decide to bomb us? The local artists reassure me: “They cannot do anything. Only if we do something first. That is why we do not publicize the festival. Only people we trust. If one little child picks up one tiny stone and throws it in their direction, then it is over.” The air is tense with each guest appearance by the military. It appears they are primarily there for surveillance- sometimes they stay in their vehicles, sometimes they walk up on foot. They ask questions “What is going on? Are you building something? Why are you here?” When they leave, they leave very slowly, stopping often to look back, or circling over a second time. It must be hard to make sense of a Donkey Fashion show or even a sing-along if you are expecting and looking for violence.

As night falls, and the moon rises, the organizers are receiving dozens of calls and texts threatening that 80 soldiers are on their way on foot to make us leave by any means necessary. While the community enjoys the fire performance, the core team scurries about to prepare for a swift exit. The ever-present danger now feels immediately pressing. The team cancels the rest of the evening’s activities, sending the children and guests home without ceremony. We pack as much as we can find in the dark. We leave the banner of artwork by the children.

At home, the core team and family debate the safety of returning the next day. It is heated and complex. Within the debate, I treasure the triumphant and encouraging perspective of one relative, a psychiatrist: “How incredible that they sent a helicopter- even with everything going on in Nablus, they never sent a helicopter. That cost them a lot of money. This is a success! And the children were happy, so so happy.

Recent elections in Israel will likely make events like these only more difficult for the families holding life together in the West Bank of Palestine. I have heard and believed all my life that it is a “complicated” and “impossible” situation between Israel and Palestine. I think of a sign from a protest for another “impossible” situation: “I stand with the most vulnerable,” and from that angle, it’s not so complicated, that is where I want to stand.

The artists of the Jabal Al Risan Art collective have their plot marked by a red sign, “Area Z,” one of the few current surviving works of art created for h.A.R.A.M. The artists tell me it is their dream that this area is redesignated as “Area Z” outside of the current allocations A, B, and C. Area Z would be protected by international law, supported by allies from abroad, an area not controlled by Israeli military, Palestinian Authority, U.S. military, or any forces of violence at all, but run by the artists- the culture bearers, those who have chosen creation rather than destruction. They would care for this land. I cannot think of better stewards.

The Festival of Forbidden Life was held in person and online October 27-29. The online event included videos from the mountain along with contributions from stellar artists all around the world who identify with and support the cause of the artists of Jabal Al Risan. You can see the full virtual festival here.

More Pictures from the Festival of Forbidden Life

"They pose and sing songs, clambering enthusiastically for the mic, for the opportunity to be heard, to express themselves, to sing their culture and their heritage, to exist freely as themselves."

Global Lab Tweet