This post offers a glimpse into the process, imagery, and questions that shaped Protest on Parade:The Unity, Ritual, and Joy of Carnival, curated as part of the larger Conjuring the Caribbean Colloquium and Performances at Georgetown University, (an immersive, week-long colloquium exploring Caribbean labor, history, religion, and carnival). Rather than recap an event that was unable to materialize, I wanted to share a sketch, an echo of what the gathering was meant to hold, and what we hope may still come to life in the future.

A Place of Home in Carnival

I was born and raised in Trinidad and Tobago, the land of oil and music. My deep connection to my native land and culture informed my collaboration with my visionary colleagues, Dr. Anita Gonzalez and Mia Massimino, who invited me to imagine Protest on Parade. Together, we asked how Carnival might be approached not only as a celebration, but as a living archive, one that carries histories of resistance, survival, and collective memory through joy, music, movement, and art. I was fortunate to interview many scholars and friends who are already researching carnival through the many different lenses that it deserves to be studied and archived. I’ve provided some of those resources in this reflection.

Rooted in African traditions, Caribbean Carnival emerged as a mode of resistance and cultural affirmation in the aftermath of slavery. Shaped over time by exchanges between African and European influences, it now exists in many forms across the region, reflecting a complex shared history.

My intention is not to present a comprehensive account of Carnival, nor to position myself as an authority on Carnival. Instead, I chose a few meaningful entry points into the tradition with an invitation for audiences to meet me there, with curiosity, reflection, and dialogue

Set Design: Gathering in the Gayelle

The circular formation evocative of the gayelle: the ring formed by onlookers where stick-fighters (batonnières) engaged in Kalenda (Calinda), a martial art dance rooted in African traditions, was more than a physical structure. It represented collective witnessing, shared responsibility, and communal presence. It also encourages the audience to participate in Caribbean cultural practice.

Photos by John Dhiel

Above this imagined gathering hovered a chandelier of color: textiles moving, swaying, sometimes in unison, sometimes independently in response to the energy below. Recognizable madras patterns recalled my connections across the Caribbean, islands where I’ve been and others that I know through my Caribbean community. These visual echoes called to mind the Pierrot Grenade, a traditional Trinidadian mas character known for wit, erudition, and sharp social commentary.

The fabric became a reminder: our histories are intertwined. This interconnectedness became even more apparent as the team met and worked on the program, sharing personal reflections on what “Conjuring the Caribbean” meant to each of us and planning through lines of questions and reflections for the suite of programming.

Protest on Parade: The Unity, Ritual and Joy of Carnival

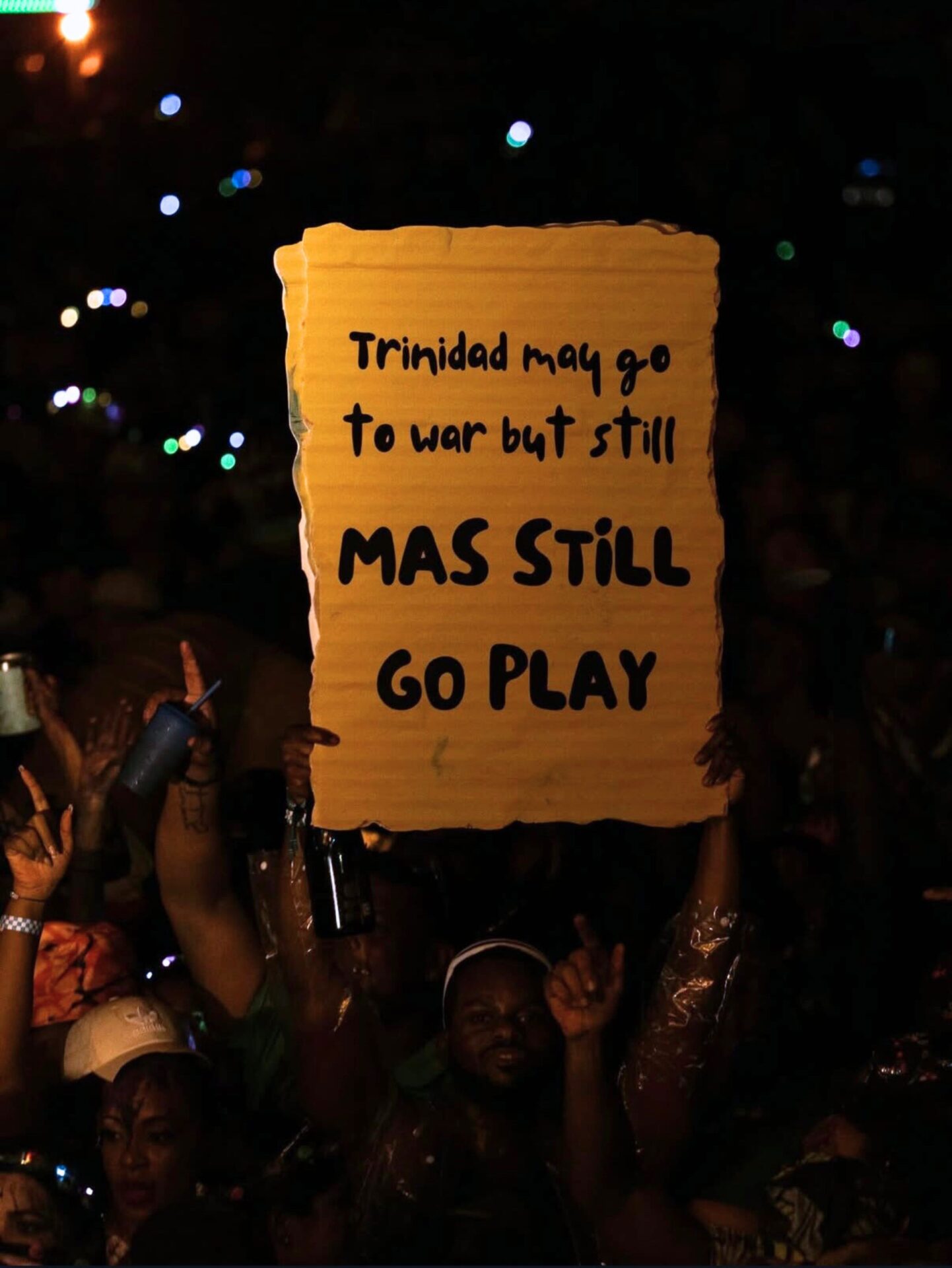

Given everything unfolding across the Caribbean today, with the geopolitical titans still angling and pitting islands against one another for capitalist gain, this Carnival feels especially meaningful, an opportunity to affirm culture, connection, and shared understanding. Carnival season is already underway in many countries around the world, with Carnival Monday and Tuesday in Trinidad and Tobago falling on February 16 and 17 this year.

This program was shaped in collaboration with artists and educators: Soka Tribe, founded by Georgetown alumna Shermica Farquhar, and with Khandeya Sheppard, steel pan musician and educator at Peabody University. Their contributions grounded the program in lived practice, reminding us that Carnival is an embodied experience.

Photo credit: @chanichans via Instagram

To bring this history to life in a different way, I’ll share with you an excerpt from the play Kambule by Pearl Eintou Springer.

The Kambule Street Pageant is performed every Carnival Friday morning just before daybreak. Since the year 2000, it has reenacted the Kambule riots of 1881, when the local population successfully resisted the British colonial government’s attempts to suppress Canboulay celebrations. The ritual includes flambeaux, stick fighting, African drumming, tamboo bamboo, traditional mas characters, and the chanting of “Five, Five, Five in the Morning,” marking the beginning of the Carnival weekend that culminates in the Las’ Lap on Tuesday.

Watch the night sky bright with fire

Flames are dancing, the Africans gather

Burning the canes, an act of resistance

In a life of sabotage and defiance

When at last they won their freedom

The Kambule retained great symbolism

1st August 1838!

Who could forget that momentous date?

Well the colonial administration

Only causing the people pure frustration

The cruel government make their play

For we not to remember we freedom day

In 1841 they say two days, not three

More than enough for we revelry

From 1844 no mask could be worn

Except on the two days agreed upon

By Ordinance 6 of 1849

The Kambule celebrations fete ban

They change the celebration from August 1st too

They put it before the Lenten season

The European Carnival is the reason

And August 1st they give to Columbus

The very man who brought slavery upon us

Still the mas

Was a source of resistance

Comfort, satire

And creativity for us

When sharing Carnival, intention matters. This rich tradition encompasses storytelling, dance, street theatre, and masquerade: often rooted in mockery, satire, and social critique born from histories of enslavement and resistance.

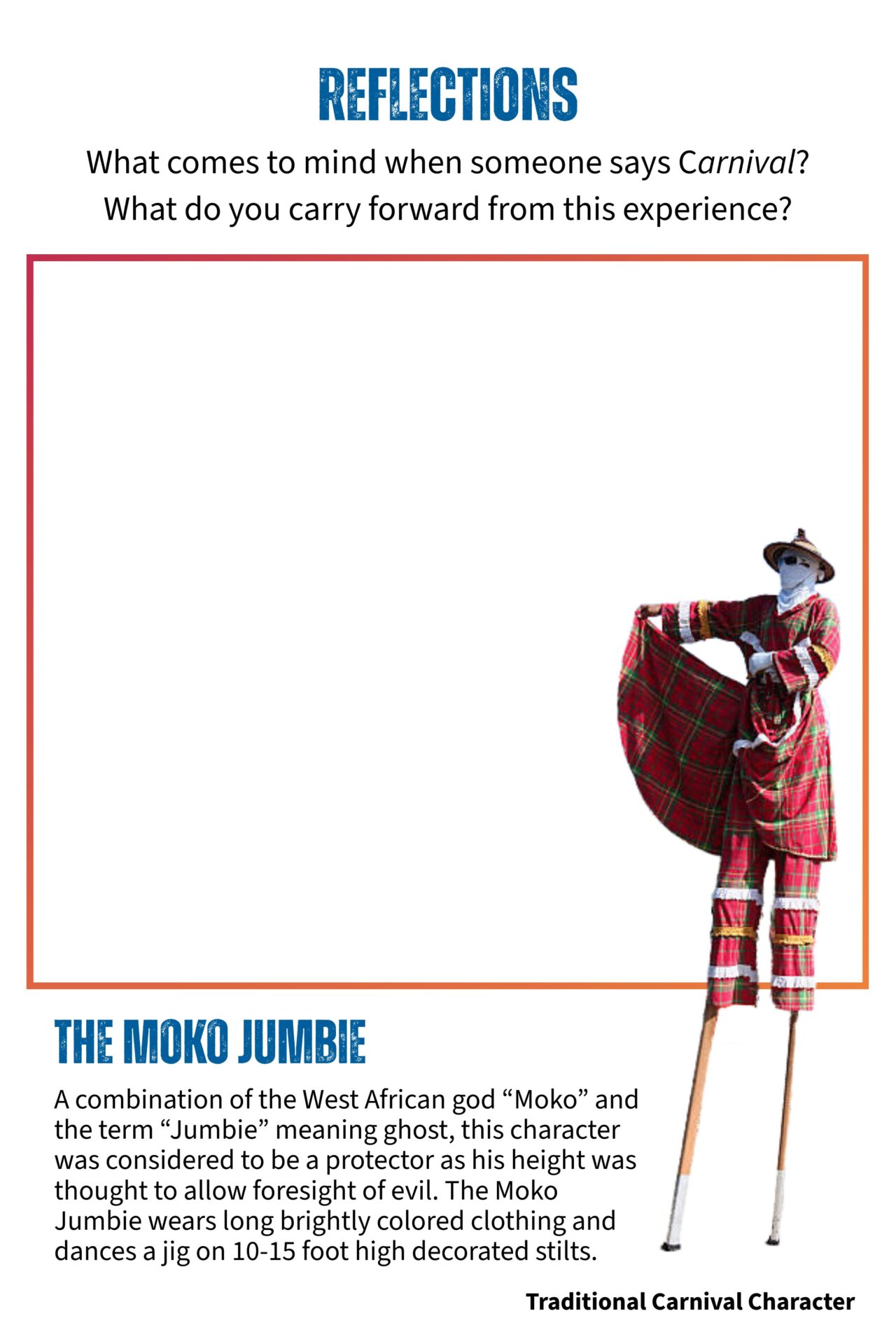

Masquerade forms:

- Ole Mas — satirical, political masquerade using “old”/ reappropriated clothing

- Traditional Mas – characters influenced by African/ Amerindian/European origins with social commentary at the root of the characters

- J’ouvert (Dirty Mas) — embodied disruption, earth, paint, resistance

- Pretty Mas — spectacle, beauty, modern Carnival industry (Beads and Bikini)

Music, too, is central to Carnival celebrations: steelpan, calypso, kaiso, each a vehicle for storytelling, survival, and collective voice. The birth of steelpan itself, the only percussive instrument to be invented in the 20th century in Trinidad and Tobago stands as an act of resistance, innovation, and community resilience.

Watch more here:

Source: Know your Caribbean

Due to snowy and icy conditions, we were unable to gather as planned. But Carnival teaches us that interruption is not erasure.

We look forward to returning to this work—in community, in motion, and in shared reflection. Please stay tuned for future ways to connect with the spirit of carnival.

People, Stories and Resources:

Kearn Williams, A Carnival Junction

Khandeya Sheppard: https://www.kaydsmusic.com/

Visit Trinidad: https://visittrinidad.tt/things-to-do/carnival/

Sharri Petti: Mas and Movies: https://scenepresents.com/blog/mas-and-movies-2026

Soka Tribe: https://www.sokatribe.com/

Carnival in photographs by Maria Nunez:

https://www.marianunes.com/f419154296